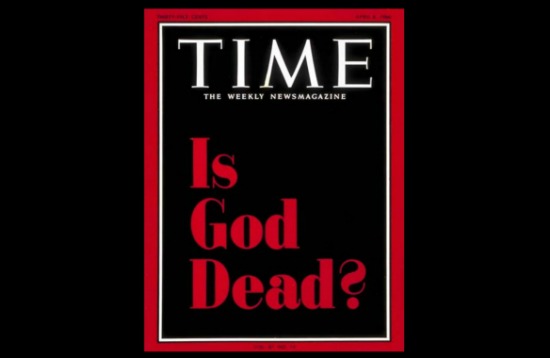

O n Good Friday in April 1966, fifty years ago this month, Time magazine published its famously controversial cover story, “Is God Dead?” Placing that stark query in bold red lettering against an all-black background, the weekly informed readers that those “three words represent a summons to reflect on the meaning of existence.” Written by Time’s religion editor, John T. Elson, the article attempted to capture the nation’s shifting theological mood from the complacent faith of the 1950s to the metaphysical confusion of the mid-1960s. The cover itself quickly became an icon of the period’s social and religious transformations—apiece with John Lennon’s suggestion that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus among contemporary youth or with Timothy Leary’s imperative to “tune in, turn on, and drop out.”

Elson framed his story as a clarion of “the new atheism” of the 1960s, a testimony to a cultural crisis of faith in which the very premise of a personal God was coming undone. In the arts, for example, he pointed to the “scrofulous hobos” of Samuel Beckett—“the anti-heroes of modern art”—who made it plain that “waiting for God” was futile “since life is without meaning.” Likewise, in contemporary Jewish philosophy, the eclipse of God in the lengthening shadow of the Holocaust remained unavoidable (Richard Rubenstein’s After Auschwitz appeared in 1966). In social anthropology as well, Elson suggested, the “politely indifferent” atheism of Claude Lévi-Strauss made “the God issue” seem like little more than an irrelevance. Even at the grassroots level of American churchgoing, there was cause for concern. With historian Martin Marty as his authority, Elson indicated that “all too many pews are filled on Sunday with practical atheists—disguised nonbelievers who behave during the rest of the week as if God did not exist.” Most portentous of all, though, was “a small band of radical theologians,” self-described Christian atheists, who were quite sure “that God is indeed absolutely dead.” This “current death-of-God group” had managed to enshrine Nietzsche’s “taunting jest” inside American Protestantism’s own theological citadels.

Elson drew attention to three academics as the principal purveyors of the death-of-God theology: Thomas J. J. Altizer, a professor of religion at Emory University and a lapsed Episcopalian; William Hamilton, a professor of theology at Colgate Rochester Divinity School and an ordained Baptist; and Paul Van Buren, a professor of religion at Temple University and an Episcopal priest. These three, along with a handful of other academics such as Gabriel Vahanian at Syracuse University, were unlikely harbingers of a trendy religious movement. Beyond occasionally connecting on the conference circuit, they were not organized in any discernible way. Taking measure of this small bunch of “existentialists,” “secularists,” and “profane mystics”—of which he was a prominent member—William Hamilton dubbed them “a loose coalition of drinking companions.” Elson’s story, along with much wider media coverage, extended the reach of this death-of-God clique well beyond hotel bars and professional meetings. Altizer especially became a celebrated spokesman for “Christian atheism”—a prophetic sloganeer who very much capitalized on the existential urgency, anguish, and exhilaration of the moment. “God has died in our time, in our history, in our existence,” Altizer proclaimed, and the collapse of traditional faith communities was the inevitable correlate of that death.

Infamous for giving cover-story visibility to the death-of-God theology, Elson’s article actually dwelled more on the possible reawakening of the divine than it did on the shock value of the new atheism. Was all this religious doubt and alienation, Elson wondered, but an indication of “a new quest for God”—one that was moving beyond ordinary church boundaries into new patterns of insight and discernment? Elson was not keen on all those seekers who “desperately turned to psychiatry, Zen or drugs” to assuage their search-for-meaning anxieties, but he could hardly deny their prevalence. Striking an ecumenical, almost post-Christian tone at the end of his piece, Elson averred that “God is not the property of the church” and that a “reverent agnosticism” toward ecclesial doctrines was now in order. Significantly, the death-of-God group, especially Altizer, warmly embraced that questing posture and took it far beyond Elson’s modest formulations.

The God-is-dead tempest had been whirling for more than half a year when Time emblazoned the controversy on its cover. By the fall of 1965 the news coverage had already become extensive. That October The New York Times reported at length on these new “radical Protestant thinkers” who were intent on reimagining Christianity without God and without “traditional church practices.” Highlighting the same trio that Elson would the next April, the Times singled out Altizer as the “most radical,” especially for his “mystical” propensities: “He rejects not only the Christian tradition,” the paper reported, “but much of Western culture to explore Eastern and primitive religious phenomena.” Less than a week later, Time magazine offered its own initial foray into “The ‘God is Dead’ Movement.” Again, it was Altizer’s “eclectic theology”—the merger of his sepulchral atheism with “a strong streak of mysticism”—that attracted particular notice. Altizer looked like a living paradox, if not oxymoron: a Christian who was an atheist, a theologian at a Methodist school who was unusually absorbed with Buddhism. A one-time candidate for the Episcopal ministry—he failed the church’s required psychiatric evaluation—Altizer had found his calling as an elegist of Christendom’s God. Confronting “absolute darkness,” he awaited the dialectical return of the sacred in transfigured form—or, put differently, the affirmation that was to arise from total negation.

After the extensive print news coverage in the fall of 1965, the death-of-God brouhaha reached a crest that winter with a pair of feature stories on the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite on back-to-back nights in February 1966. Altizer was again the center of attention, pronouncing God’s death with a wild-eyed, prophetic confidence. The CBS coverage managed to add a new theatrical wrinkle, shocking many viewers by showing “a funeral service for God,” a requiem written by an assistant professor at North Carolina Wesleyan College. Focusing especially on the face of an innocent-looking undergraduate as she chanted the “God is dead” mantra, CBS lingered over the bleak liturgy that Altizer and his colleagues had inspired: “He was our guide and our stay/He walked with us beside still waters/He was our help in ages past … He is gone, He is stolen by darkness … Heaven is empty.”

Two months later the death-of-God commotion reached its cultural climax with Time magazine’s cover story. By then, Newsweek and U.S. News and World Report had also given concerted attention to the hullabaloo. The excitement finally played itself out over the summer, slowly dwindling away after Altizer’s especially dismal reception on The Merv Griffin Show that August. Hissed and booed, he found the clock running out on his fifteen minutes of pop-culture celebrity. Within a year or two, his radical theology looked like it had been nothing so much as a passing fad. “Pop Theology via TV,” the Christian Century dubbed one of Altizer’s performances; he had offered little more than “adolescent daydreaming,” the sober mainline Protestant weekly sniped, on par with the espionage show “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” For its part, Christianity Today assured its evangelical readership in May 1967 that “the death-of-God stir has passed like an overnight storm” and that Altizer’s “bizarre and aberrational” claims would “soon be forgotten” in the face of the enduring proclamation of the gospel.

Fifty years on, the whole death-of-God hubbub warrants reexamination. The advent of the Christian atheists revealed a fissured religious terrain: evangelicals seething over the God-is-dead heresy as well as the liberal betrayals of the Supreme Court; secularists, atheists, and humanists wishing these radical theologians could get over their lingering Christian hang-ups; mainline Protestants, by turns, proud and wary of the existentialist dissent their theological liberalism had generated; and sundry seekers inviting the death-of-God fraternity to join them in a spiritual counterculture of heady, wide-ranging exploration.

Altizer himself hardly needed that last invitation. After failing to become an Episcopal priest, Altizer had channeled his energies into PhD work in theology and the history of religions at the University of Chicago, ultimately coming under the sway of Mircea Eliade’s comparative, esoteric vision of the field. Altizer’s first book, published in 1961, was on Oriental Mysticism and Biblical Eschatology; his second book, which appeared two years later, was entirely devoted to an exposition of Eliade’s work, including the “archaic ontology” of shamanism, with sections on alchemy and yoga to boot. Shaped by his own early visionary experiences of Satan and God, Altizer counted himself a “disciple” of Eliade’s, even reporting that he underwent—some years later—a “contemporary shamanic initiation” at the Chicago professor’s own hands during a ghostly gathering in Hyde Park. The “Is God Dead?” sensation of 1965-1966 had many sources and upshots. Certainly, it gave prominence to a “new atheism”; even more, though, it amplified the diffuse seeker sensibilities of the era and blessed a churchless quest for the sacred through and beyond the death of God.

The death-of-God provocateurs generated plenty of outrage, particularly from Bible-believing Protestants, including a good number of southern Methodists who could not fathom that the theology’s most visible spokesman was employed at one of their church-related colleges. Altizer’s correspondence files are filled with letters from aggrieved evangelicals, several of whom included soul-saving tracts, handwritten biblical extracts in red lettering, or even wry condolence cards for the professor’s loss of his Father (God). One writer, C. A. Kelly, from South Carolina, struck a relatively loving tone in a letter he wrote to Altizer after seeing him on Walter Cronkite’s news program:

Mr. Altizer you should not say God is dead … We Christians who have had an experience of Salvation through the atoning blood of Jesus Christ know different. A dead God could not have saved my soul when all hope was gone. It was a living Christ that came into my heart April 16, 1950 and delivered me from alcohol, tobacco, a cursing tongue and all the other filthy habits of the flesh and the devil … You may not believe it, you may not accept it but in spite of [your] belief or I should say unbelief [,] God still loves you.

Many of Altizer’s correspondents simply wanted to witness to him, to tell him about their own experiences of a living God, and to let him know that salvation could yet be his as well. “I would like to ask you to turn away from your Phd degree, or BD degree,” one North Carolinian exhorted, “and for a moment consider the B.A. Degree given to those who are Born Again by the Holy Ghost.”

Other evangelicals were far less prayerful in approach, hoping rather that God would swiftly punish Altizer—along with various other enemies of the faith and the nation. “You and Martin Luther King Jr. have several things in common,” a preacher from Brownsville, Texas, informed Altizer. “You are ‘wolves in sheep’s clothing’ … Your four hands will be bloodied by the lives of those you two have deceived and encouraged to go to Hell with you all. One day, my God will triumph!” A correspondent from Kansas City added to the chorus of hostility: “We have too many of your kind in our schools and colleges today. This country was built by Christians who had faith and believed in God … Maybe Russia would be your choice!”

For many white evangelicals, the God-is-dead furor played on a crescendo of fears—of godless communism, civil-rights activism, and liberal secularism, made tangible by atheist college professors and by the Supreme Court in its recent decisions against prayer and Bible reading in the public schools. Altizer became the perfect bȇte noir—a treasonous blasphemer of the nation’s most elemental pieties, more threatening in some ways than the atheist activist Madalyn Murray O’Hair because his subversive rhetoric arose from within the Protestant fold. “I became one of the most hated men in America,” Altizer reflected four decades later in his theological memoir Living the Death of God, published in 2006. Judging from the conservative Christian hate mail he received, he was not inflating his infamy by much. “You are one of Satan’s people—you are Anti-Christ,” a woman from Wisconsin raged against Altizer. “True Christians want to kick you right out of the U.S.”

At the other end of the religious spectrum were Unitarians, humanists, secularists, and outright atheists who were delighted to have God’s demise getting so much attention, even if the funeral retained a distinctly Protestant tenor. “It’s high time,” the leader of a Unitarian fellowship in Savannah wrote to Altizer, “we replaced the sentimental ideas about God and started practicing a universal religion based on respect for all mankind and an Ultimate Concern for all Life.” A Christianity shorn of God but not of its social-justice imperative resonated with many American secularists and humanists—not exactly a large contingent, of course, but organized enough to sustain small federations such as the American Ethical Union and to issue the occasional manifesto of progressivist striving.

Others were less impressed, though, with the way the Christian atheists held onto Jesus as an ethical paragon for radical theology. “Congratulations in having given the heave-ho to that worst of Theological frauds—God,” a former colleague at Wabash College wrote Altizer before advising him to take a harder look at “Christ’s ethical system.” It “seems rather second rate to me,” his old associate wrote. “So why the ‘Christian’ atheism?” Other letter-writers wanted to push Altizer and company into more obviously secular political postures. A Georgia nonbeliever asked:

Do you think it’s right for the government to keep putting “In God We Trust” on our money, when it spends 50 billion dollars a year for man made military protection? … I think it is a bad thing that the American feeling is that everybody should belong to some religious group, and that agnostics are looked down on as second class citizens. I think the constitution of the U.S. should read freedom from religion.

To have this new brand of atheism featured in Time or on the CBS Evening News gave heart to a freethinking minority long habituated in the Cold War to the routine association of their secularist dissent with godless communism.

G. Vincent Runyon, one of the humanists and rationalists who wrote Altizer, wanted to nudge the death-of-God theologians in the direction of a more thoroughgoing atheism. A graduate of Drew Theological Seminary in 1925, Runyon had been a Methodist preacher of the modernist variety for twelve years in New York before being won over by the “constructive” humanism he encountered initially among Unitarians. He left the Methodist pulpit and found fellowship instead with the Los Angeles Society of Humanists. “There are many roads to atheism but I came in through the door of Humanism,” Runyon observed in his short memoir, Why I Left the Ministry and Became an Atheist, published in 1959, six years before he reached out to Altizer. As a materialist, Runyon did not understand the mystical yearning that persisted among the Christian atheists for the return of God or why they continued to patronize Protestant journals like the Christian Century rather than the American Rationalist. Mostly, though, Runyon wanted to express his sincere appreciation to Altizer and his companions for prompting such wide-ranging inquiry into the death of God in a country that seemed otherwise reflexively God-affirming. For Runyon, all the media attention given to Christian atheism pointed to a religious journey rarely afforded that kind of cultural recognition—the passage out of Protestantism into open nonbelief. Runyon, in short, spoke for the irreligious segment of the population long before sociologists had invented the “Nones.”

For their part, mainline Protestants—at least, at leadership levels—were caught in the middle, disinclined to offer an evangelical altar call or a ringing post-Christian endorsement. Largely at home with the liberal modernist values of academic freedom, intellectual innovation, and artistic creativity, ecumenical Protestants defended Altizer from those who thought he had no business teaching at a church-related college. He was not going to get fired from Emory on their watch, even if his presence jeopardized the school’s recently announced capital campaign. Like the young Methodist theologian Thomas Ogletree (eventual dean of Yale Divinity School) who wrote a whole primer on the controversy for puzzled churchgoers, ecumenical Protestants mostly responded with curiosity and engagement, even as they regretted the journalistic sensationalism that Altizer especially invited. The tagline of the National Council of Churches’ television advertisement, which ran in response to the whole melee, was purposefully irenic, almost anemically so: “Keep in circulation the rumor that God is alive.” For ecumenical Protestants, already attuned to Paul Tillich and Rudolf Bultmann, the radicals rarely seemed so wildly radical as they announced themselves to be. The Methodist youth magazine, motive, embraced the new theology with puckish glee, running its own mock obituary under the headline: “God Is Dead in Georgia: Eminent Deity Succumbs during Surgery—Succession in Doubt as All Creation Groans.” The questioning and questing sensibility that Altizer represented already had deep roots within ecumenical Protestantism. A syllabus featuring Blake, Melville, Nietzsche, Camus, and Ingmar Bergman was not going to scare off too many in this constituency.

In 1975, when Altizer’s lieutenant William Hamilton looked back at “The Death of God after Ten Years” for the Christian Century, he positioned the radical theology’s significance not in terms of its impact on a new atheism or a transformed Protestantism. Instead, he highlighted the ways in which it had been “profoundly connected to the outburst of American religiosity, Oriental and otherwise, in the late 1960s.” The controversy, Hamilton suggested, had helped fuel the post-Christian, pluralistic, and eroticized spiritual strivings on the countercultural left. (The erotic piece was important to Hamilton; he liked to talk up his time spent on the “sex circuit” promoting the “unrepressed life” on college campuses, including a gig with Hugh Hefner at Johns Hopkins.) “To affirm the death of God,” Hamilton wrote, was “to remove the Mosaic-Calvinist censor from the door of the Holy of Holies” and to break open the white, masculine, Protestant world of divinity. Without that old custodian of the sacred in place, Hamilton surmised, American religiosity had been able to take wing away from the churches and alight on all kinds of “new polytheisms and syncretisms.”

It goes without saying that the death-of-God theology was more symptom than cause of this wider spiritual and metaphysical ferment, but Hamilton was nonetheless right to highlight the dialectical connections. The insistent emphasis on the metaphor of God’s death—the irretrievable loss of the divine in the common experience of many American Christians (who were usually universalized as “modern man”)—was paired with a hopeful posture of revolutionary possibility, that substantive change was imminent in the religious as much as the political and social realms. God would be back, in other words, just not as the guardian of mainline Protestantism’s cultural authority. The “homeland” of Christian faith, as Altizer saw it, had been lost, but “the epiphany of the religious Reality” beckoned the grieving inquirer away from modern nihilism into explorations of Buddhism, mysticism, archaic religions, alchemy, and “various forms of Indian Yoga.” For Altizer, Eliade’s initiate, America’s desacralized Christianity was to be reborn through its encounter with “the universal sacred,” and modern theological inquiry was to be revivified through the primordial ontology revealed in the history of religions.

Altizer had many correspondents who agreed with him that the time had come for “a radical quest for a new mode of religious understanding.” Often, though, they thought he had fallen short of exploring territory that needed to be explored. Alvin Miller wrote from nearby Decatur to tell Altizer of how he had long stared into the existentialist void and eventually found rescue through a multilayered “quest for the Spiritual.” He wondered why Altizer had not done more to engage Zen Buddhism and the search for “Totality by not-searching.” “In the beginning mountains are mountains and rivers are rivers,” Miller wrote, echoing a passage from Alan Watts’s The Way of Zen (1957). “Then a point comes when the mountains are not mountains and the rivers are not rivers. But with time the mountains are once again mountains and the rivers are again rivers.” The Zennists, as Miller called them, very much needed to be part of radical theology’s expanded spiritual horizon.

Other correspondents, of course, had different recommendations for Altizer’s announced quest. Had he read Swedenborg, Aldous Huxley, and the British theosophist Paul Brunton? How about Swami Vivekananda, Thomas Merton, and Huston Smith? It was not only additional reading, but also novel practices and experiments that were recommended. One of Altizer’s former undergraduates, who had gone on to get his PhD in psychology from Berkeley, wrote to thank his professor for sparking his initial spiritual curiosities—a trek that had led him from Zen to LSD to an Indonesian meditative movement known as Subud. Likewise, another former student, who had also migrated from Emory to California for graduate work, fondly recalled the world religions course he had taken with Altizer and then remarked: “I thought I’d drop you a note about something of mutual interest—mysticism—or to spell it another way—LSD. Yes, the LSD experience and the mystical experience are much the same thing. It is completely preposterous getting religion out of a pill, I know, but nevertheless.” New realms of consciousness were opening up, and his former student felt sure that Altizer very much deserved to be among “the enlightened.” For these correspondents, Altizer had become a celebrated spokesman for spiritual seeking beyond familiar religious institutions and moribund theologies. One correspondent summed up the entire drift of these letters in his sign-off to Altizer: “Yours for more honest searching and less ecclesiastical Bull shit[t]ing.”

No one more richly embodied the interconnections between the God-is-dead moment and post-Christian spiritual striving than the beatnik-hippie poet George Dowden, another of Altizer’s correspondents. An American expatriate living in England, Dowden was especially devoted to Walt Whitman and Allen Ginsberg; like them, he was adept at playing the role of the poet-prophet, the bearer of a literary and religious counterculture that courted the obscene and the blasphemous. Dowden sent Altizer a mimeographed copy of his underground poem Renew Jerusalem, which would be published in book form three years later in 1969. A section entitled the “Novum Theologicum” saluted the “latest theological avant-garde”—including Altizer, Hamilton, and Paul Van Buren by name—and proclaimed the passing of both the “Executive God” and “the white man’s religion.” Dowden lingered for contrast over the youthful seekers of his own generation who had rediscovered the divine in the “bodysoul mystery” and in the ecstasy of the Whitmanian artist.

The renewed Jerusalem that Dowden imagined would be orgiastic and psychedelic—and spiritually diverse. Near the poem’s opening he is in a monastery, collecting bugs as they come in an unscreened abbey window: “Pure task as I meditate on the matter—Benedictine Pent[e]costal Christian Hebrew Buddhist Hindu Moslem Taoist Zoroastrian Christian Voodoo Jain Native Church of American Indian League for Spiritual Discovery yoga.’’ Running all the religious possibilities together—with no commas to separate them—the poet then sees himself reflected naked in the abbey window, his body adorned only “with colored glass beads—spiritual jewels.” A few years later Dowden would find himself far removed from an English abbey, a “Sixties Man” at an ashram in India, reinventing himself once again through a year-long spiritual journey with the acclaimed guru Swami Muktananda, popularizer of Siddha Yoga as a meditative path of self-realization. Not surprisingly, Dowden found Altizer’s theological musings rather timid on the whole. “I of course do not find you radical enough,” the poet informed the professor, but he did find him sufficiently provocative to discern a fellow traveler in a heterogeneous, post-Christian landscape.

“Is God Dead?”—the Time cover augured less a new atheism than a transformed American religious scene. The bells were tolling not for Christendom’s God but for the ecumenical Protestant establishment. Embodying a moment of theological and cultural crisis, Altizer’s promulgation of Christian atheism proved a last hurrah for the public voice of mainline Protestantism. Lacking the establishment clout of Reinhold Niebuhr, Paul Tillich, or G. Bromley Oxnam—all Time cover honorees in the years following World War II—Altizer became a Warhol-like figure in his brief fling of cultural notoriety. Ecumenical Protestant intellectuals became much easier to ignore after the very public requiem that Altizer and his companions staged in 1965 and 1966. Over the next decade and a half, it would be resurgent evangelicals who became media darlings; the Year of the Evangelical arrived in 1976. Ronald Reagan, who was elected governor of California in November 1966 a half year after Time’s cover story, sealed the ascent of the Religious Right with his presidential victory in 1980.

Conservative evangelicals, however, were not the only ones to benefit from the religious and cultural space opened up by the dwindling authority of liberal Protestants. The ascendancy of those who identify as spiritual-but-not-religious, as unaligned seekers, points to an equally momentous development of the last 50 years, and, in that context, Altizer and his companions look less like fleeting celebrities than clear-eyed seers. The spirituality-without-religion phenomenon had deep cultural roots, of course, and innumerable sources—from Emersonian transcendentalism to 12-step recovery regimens. But, the death-of-God controversy provided an important impetus at a critical moment in the diffusion of that religious outlook. “An angry young (sha)man,” Altizer’s friend William Hamilton had called him affectionately, and Emory’s heretical professor was certainly as much Eliade’s disciple as Nietzsche’s madman. Likewise, the Time cover story of a half century ago—with its bold query, “Is God Dead?”—was not so much a prognostication of the latest New Atheists; instead, it foreshadowed the nation’s proliferating questors for the sacred apart from the church and its departed deity.

Leigh E. Schmidt is on the faculty of the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis. His latest book, Village Atheists: How America’s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation, will appear this fall from Princeton University Press. He gratefully acknowledges permission to quote materials for this essay from the Thomas J. J. Altizer Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.